載入中..請稍候..

32.~36. 為題組。閱讀甲、乙、丙、丁文,回答 32.~36.題。

甲、 每個時代是否有每個時代的文風?若有,我們又是根據什麼來區分這些時代?是因為它們有著特異的政治條件或社會狀況?或者我們相信有一種神祕的時代精神貫穿於其間,使一切文化事物都沾染了特殊的時代的印記?但其實我們了解每一個作品都與其他的作品不同,即使是同一個作者的同一個時期,甚至同一天的作品,假如它們是作品而不是複印,它們都必然不會完全一樣。因此所有的概括形容,討論的都是方便的分類,用類型的近似來取代個別作品的獨異實體。因此我們在作概括性的討論之際,我們往往正是在虛構,甚至是創造了,若加以追根究柢終不免是獨斷的一種分類,它永遠得面對一種質疑:這些獨斷的分類真的代表事物或歷史的原貌?尤其具有評價意味的文藝作品,哪些作品來代表那個獨特的時代,更是可以因為信仰、品味、興趣與立場的差異,而人言人殊。(柯慶明〈試論漢詩、唐詩、宋詩的美感特質〉)

乙、 姚斯曾說道:「文學的歷史是一種美學接受和生產的過程,這個過程必須通過接受的讀者、反思的批評家和再創作的作家將過去的作品加以實現才能進行。」的確,讀者並非全然被動的接受主體,隨著前理解的差異與變化,也自然產生不同的期待視野。在臺灣文人閱讀與接受唐宋詩的過程中,可以看到接受主體對文本的詮釋、理解與再創造,都展現不同的詮釋空間。就「不分唐宋」的評賞態度而言,林占梅率先表示的「遣興不分唐宋格」,大有揉合唐宋詩歌的品評立場,這樣的評賞姿態之所以可以成為臺灣文人的群體共識,肇因於對詩歌本質的模糊認識,由於臺灣文人在清領道光、咸豐時期才逐漸增多,其文學觀還停留在學習與摸索的階段,故唐宋詩之於臺灣文人而言,各有詩學典範值得效法,所謂「性情相合即師之」,不必刻意區分高下。

(余育婷〈從「不分唐宋」到「詩學晚唐」:清代臺灣文人對唐宋詩的審美態度〉)

丙、安穩高詹事,兵戈久索居。時來如宦達,歲晚莫情疏。

天上多鴻雁,池中足鯉魚。相看過半百,不寄一行書? (杜甫〈寄高三十五詹事〉)

高三十五詹事:即高適。安史之亂因得罪權臣李輔國,被貶為太子少詹事。與杜甫曾同朝為臣。

丁、我居北海君南海,寄雁傳書謝不能。桃李春風一杯酒,江湖夜雨十年燈。

持家但有四立壁,治病不蘄三折肱。想得讀書頭已白,隔溪猿哭瘴煙藤。

(黃庭堅〈寄黃幾復〉)

黃幾復與黃庭堅:黃幾復早年與黃庭堅交往密切,其才德頗受黃庭堅稱道。黃幾復登科後遠赴嶺

南做官,長達十年。黃庭堅,早年以詩文受知於蘇軾,為蘇門四學士之一。後人奉其為江西詩派

的代表人物,此外詞與書法的成就也頗為後世稱頌。

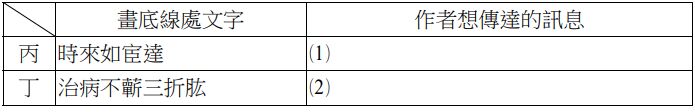

35. 參照丙、丁二詩畫底線處文字,二詩作者分別想要傳達什麼訊息?( (1)(2)各占 2 分,作答

字數: (1)(2)各 20 字以內。)

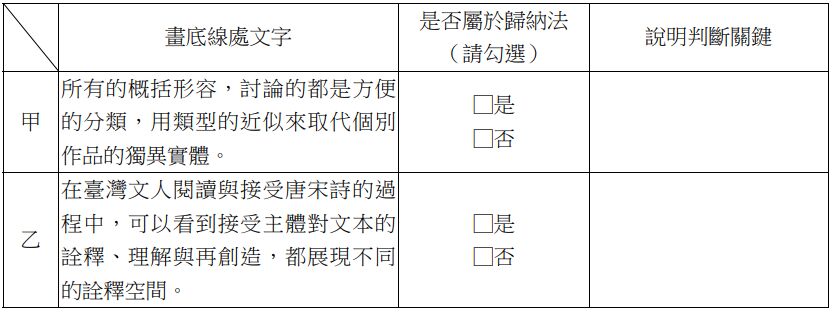

(2)請就甲、乙二文畫底線的文字判斷「討論文學表現的方法」是否屬於歸納法,並說明判

斷關鍵是什麼?(共 4 分,甲、乙各占 2 分。勾選與判斷說明合併計算,僅勾選未說明

或勾選錯誤者不給分。甲、乙判斷說明的作答字數:各 10 字以內。)

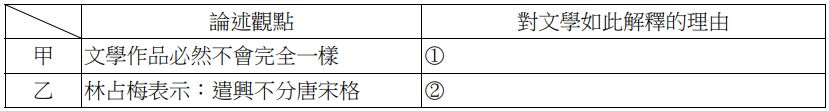

33. 請依據甲、乙二文,回答下列問題:

(1)甲文認為「文學作品必然不會完全一樣」、乙文指出「林占梅表示:遣興不分唐宋格」,

請分別說明二者對文學如此解釋的理由(共 4 分,①②各占 2 分,作答字數:①②各 10

字以內。)

Passage II

When I first encountered the name of the city of Stockholm, I little thought that I would ever visit it, never mind end up being welcomed to it as a guest of the Swedish Academy and the Nobel Foundation. At the time I am thinking of, such an outcome was not just beyond expectation: it was simply beyond conception. In the nineteen forties, when I was the eldest child of an ever-growing family in rural Co. Derry, we crowded together in the three rooms of a traditional thatched farmstead and lived a kind of den-life which was more or less emotionally and intellectually proofed against the outside world. It was an intimate, physical, creaturely existence in which the night sounds of the horse in the stable beyond

one bedroom wall mingled with the sounds of adult conversation from the kitchen beyond the other. We took in everything that was going on, of course - rain in the trees, mice on the ceiling, a steam train rumbling along the railway line one field back from the house - but we took it in as if we were in the doze of hibernation. Ahistorical, pre-sexual, in suspension between the archaic and the modern, we were as susceptible and impressionable as the drinking water that stood in a bucket in our scullery: every time a passing train made the earth shake, the surface of that water used to ripple delicately, concentrically, and in utter silence.

But it was not only the earth that shook for us: the air around and above us was alive and signaling too. When a wind stirred in the beeches, it also stirred an aerial wire attached to the topmost branch of the chestnut tree. Down it swept, in through a hole bored in the corner of the kitchen window, right on into the innards of our wireless set where a little pandemonium of burbles and squeaks would suddenly give way to the voice of a BBC newsreader speaking out of the unexpected like a *deus ex machina*. And that voice too we could hear in our bedroom,transmitting from beyond and behind the voices of the adults in the kitchen; just as we could often hear, behind and beyond every voice, the frantic, piercing signaling of Morse code.

We could pick up the names of neighbors being spoken in the local accents of our parents, and in the resonant English tones of the newsreader the names of bombers and of cities bombed, of war fronts and army divisions, the numbers of planes lost and of prisoners taken, of casualties suffered and advances made; and always, of course, we would pick up too those other, solemn and oddly bracing words, "the enemy" and "the allies." But even so, none of the news of these world-spasms entered me as terror. If there was something ominous in the newscaster's tones, there was something torpid about our understanding of what was at stake; and if there was something culpable about such political ignorance in that time and place, there was something positive about the security I inhabited as a result of it.

50. Which of the following statements is NOT true about the author?(A) He grows up in a farm.(B) As a child, he enjoys listening to the radio(C) He is invited by the Swedish Academy to visit Stockholm.(D) His childhood memory is overshadowed by the fear of war.

49. The "war" mentioned in paragraph 3 is most likely _____.(A) World War I(B) World War II(C) The Vietnam War(D) The Anglo-Irish War

48. The phrase "deus ex machina" in paragraph 2 most likely refers to ____

(A) a secret ritual

(B) a person who talks very fast

(C) something that happens out of the blue

(D) a device for recording sounds