活動名稱

【解題達人! We want you!】

活動說明

阿摩站上可謂臥虎藏龍,阿摩發出200萬顆鑽石號召達人們來解題!

針對一些題目可能有疑問但卻缺少討論,阿摩主動幫大家尋找最佳解!

懸賞試題多達20萬題,快看看是否有自己拿手的科目試題,一旦你的回應被選為最佳解,一題即可獲得10顆鑽石。

懸賞時間結束後,只要摩友觀看你的詳解,每次也會得到10顆鑽石喔!

關於鑽石

如何使用:

- ✔懸賞試題詳解

- ✔購買私人筆記

- ✔購買懸賞詳解

- ✔兌換VIP

(1000顆鑽石可換30天VIP) - ✔兌換現金

(50000顆鑽石可換NT$4,000)

如何獲得:

- ✔解答懸賞題目並被選為最佳解

- ✔撰寫私人筆記販售

- ✔撰寫詳解販售(必須超過10讚)

- ✔直接購買 (至站內商城選購)

** 所有鑽石收入,都會有10%的手續費用

近期考題

【非選題】

【題組】 ⑴請以外國的經驗,論述其他國家如何因應並防範針對運輸系統的威脅與攻擊。(10 分)

一、過去曾有人於高鐵列車上放置行李炸彈,臺北捷運列車上亦曾發生殺人事件。日本

東京地鐵、倫敦地鐵、莫斯科地鐵曾遭受施放毒氣或是恐怖攻擊,其中以英國倫敦

經歷了最多次數的破壞與攻擊。

【題組】 ⑴請以外國的經驗,論述其他國家如何因應並防範針對運輸系統的威脅與攻擊。(10 分)

【非選題】

二、土地登記規則第57條第1項第3款規定:「有下列各款情形之一者,登記機關應以書面敘明理由及法令依據,駁回登記之申請:……三、登記之權利人、義務人或其與申請登記之法律關係有關之權利關係人間有爭執。……。」此規定所稱「登記之權利人、義務人或其與申請登記之法律關係有關之權利關係人間有爭執」之意涵為何?又,假設甲於107年4月1日以遺囑指定其所有A土地之處分方式,並指定乙為遺囑執行人。108年10月15日甲死亡後,乙檢具該遺囑及其他登記申請書類文件,向登記機關申辦A土地之遺囑執行人登記。於登記機關審查期間,甲之繼承人丙,質疑該遺囑之真正,爰向登記機關提出異議。於此設例情形,登記機關可否依土地登記規則第57條第1項第3款規定駁回乙之遺囑執行人登記申請?以上二問,請綜合闡釋說明之。

二、土地登記規則第57條第1項第3款規定:「有下列各款情形之一者,登記機關應以書面敘明理由及法令依據,駁回登記之申請:……三、登記之權利人、義務人或其與申請登記之法律關係有關之權利關係人間有爭執。……。」此規定所稱「登記之權利人、義務人或其與申請登記之法律關係有關之權利關係人間有爭執」之意涵為何?又,假設甲於107年4月1日以遺囑指定其所有A土地之處分方式,並指定乙為遺囑執行人。108年10月15日甲死亡後,乙檢具該遺囑及其他登記申請書類文件,向登記機關申辦A土地之遺囑執行人登記。於登記機關審查期間,甲之繼承人丙,質疑該遺囑之真正,爰向登記機關提出異議。於此設例情形,登記機關可否依土地登記規則第57條第1項第3款規定駁回乙之遺囑執行人登記申請?以上二問,請綜合闡釋說明之。

【非選題】

【題組】(二)組織再造用於政府部門的可行性為何?【10 分】

題目二:

於 90 年代開始盛行的組織再造(organization re-engineering)是一項新的管理思潮與方

法,截至目前為止,各國皆不定期地分階段進行組織再造工程,請問:

【題組】(二)組織再造用於政府部門的可行性為何?【10 分】

【非選題】

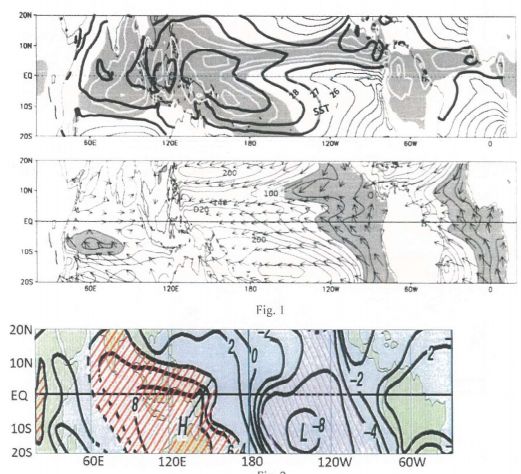

【題組】 a. Mark on Fig. 2 where convergence and divergence occurs and describe concisely the Walker and Hadley circulation based on the figure and dynamic arguments. [10pt]

2. Figure 2 shows the sea-level pressure in the tl Nino condition. (total 20 points]

【題組】 a. Mark on Fig. 2 where convergence and divergence occurs and describe concisely the Walker and Hadley circulation based on the figure and dynamic arguments. [10pt]

【非選題】

【題組】 1. Summarize Zuboff's argument in no more than 200 words. (40%)

Read the following excerpts from Shosbana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism:

Google was incorporated in 1998, founded by Stanford graduate students Larry Page and Sergey Brin.... . From the start, the company embodied the promise of information capitalism as a liberating and democratic social force that galvanized and delighted second-modernity populations around the world.

Thanks to this wide embrace, Google successfully imposed computer mediation on broad new domains of human behavior as people searched online and engaged with the web through' a growing roster of Google services. As these new activities were informated for the first time, they produced wholly new data resources. For example, in addition to key words, each Google search query produces a wake of collateral data such as the number and pattem of search terms, how a query is phrased, spelling, punctuation, dwell times, click patterns, and location.

Early on, these behavioral by-products were haphazardly stored and operationally ignored.... Google's engincers soon grasped that the continuous flows of collateral behavioral data could turn the search engine into a recursive leamning system that constantly improved search results and spurred product innovations such as spell check, translation, and voice recognition.

Google was incorporated in 1998, founded by Stanford graduate students Larry Page and Sergey Brin.... . From the start, the company embodied the promise of information capitalism as a liberating and democratic social force that galvanized and delighted second-modernity populations around the world.

Thanks to this wide embrace, Google successfully imposed computer mediation on broad new domains of human behavior as people searched online and engaged with the web through' a growing roster of Google services. As these new activities were informated for the first time, they produced wholly new data resources. For example, in addition to key words, each Google search query produces a wake of collateral data such as the number and pattem of search terms, how a query is phrased, spelling, punctuation, dwell times, click patterns, and location.

Early on, these behavioral by-products were haphazardly stored and operationally ignored.... Google's engincers soon grasped that the continuous flows of collateral behavioral data could turn the search engine into a recursive leamning system that constantly improved search results and spurred product innovations such as spell check, translation, and voice recognition.

...

At that early stage of Google's development, the feedback loops involved in improving its

Search functions produced a balance of power: Search needed people to learn from, and

people needed Search to learn from. This symbiosis enabled Google's algorithms to learn and

produce ever-more relevant and comprehensive search results. More queries meant more

learning; more learning produced more relevance. More relevance meant more searches and

more users.. . The Page Rank algorithm, named-after its founder, had already given Google a

significant advantage in identifying the most popular results for queries. Over the course of

the next few years it would be the capture, storage, analysis, and leamning from the

by-products of those search queries that would turn Google into the gold standard of web

search.

The key point for us rests on a critical distinction. During this early period, behavioral data

were put to work entirely on the user's behalf. User data provided value at no cost, and that

value was reinvested in the user experience in the form of improved services: enhancements

that were also offered at no cost to users. Users provided the raw material in the form of

behavioral data, and those data were barvested to improve speed, accuracy, and relevance and

to help build ancillary products such as translation. I call this the behavioral value

reinvestment cycle, in which all behavioral data are reinvested in the improvement of the

product or service.

...

This helps to explain why it is inaccurate to think of Google's users as its customers: there is

no economic exchange, no price, and no profit. Nor do users function in the role of workers:

When a capitalist hires workers and provides them with wages and means of production, the

products that they produce belong to the capitalist to sell at a profit. Not so here. Users are not

paid for their labor, nor do they operate the means of production, as we'll discuss in more

depth later in this chapter. Finally, people often say that the user is the "product." This is also

misleading, and it is a point that we will revisit more than once. For now let's say that users

are not products, but rather we are the sources of raw-material supply. As we shall see,

surveillance capitalism's unusual products manage to be derived from our behavior while

remaining indifferent to our behavior. Its products are about predicting us, without actually

caring what we do or what is done to us.

To summarize, at this early stage of Google's development, whatever Search users

inadvertently gave up that was of value to the company they also used up in the form of

improved services. In this reinvestment cycle, serving users with amazing Search results

"consumed" all the value that users created when they provided extra behavioral data. The

fact that users needed Search about as much as Search needed users created a balance of

power between Google and its populations. People were treated as ends in themselves, the

subjects of a nonmarket, self-contained cycle that was perfectly aligned with Google's stated

mission "to organize the world's information, making it universally acce essible and useful."'

By 1999, despite the splendor of Google's new world of searchable web pages, its growing

computer science capabilities, and its glamorous venture backers, there was no reliable way to

turn investors' money into revenue. The behavioral value reinvestment cycle produced a very

cool search function, but it was not yet capitalism. For all their genius and principled

insights, Brin and Page could not ignore the mounting sense of emergency. By December

2000, the Wall Street Journal reported on the new "mantra" emerging from Silicon Valley's

investment community: "Simply displaying the ability to make money will not be enough to

remain a major player in the years ahead. What will be required will be an ability to show

sustained and exponential profits."

...

At Google in late 2000, it became a rationale for annulling the reciprocal relationship that existed betwe een Google and its users, steeling the founders to abandon their passionate and public opposition to advertising.... To meet the new objective, the behavioral value reinvestment cycle was rapidly and secretly subordinated to a larger and more complex undertaking. The raw materials that had been solely used to improve the quality of search results would now also be put to use in the service of targeting advertising to individual users. Some data would continue to be applied to service improvement, but the growing stores of collateral signals would be repurposed to improve the profitability of ads for both Google and its advertisers. These behavioral data available for uses beyond service improvement constituted a surplus, and it was on the strength of this behavioral surplus that the young company would find its way to the "sustained and exponential profits" that would be necessary for survival. Thanks to a perceived cmergency, a new mutation began to gather form and quietly slip its moorings in the implicit advocacy-oriented social contract of the firm's original relationship with users.

...

At Google in late 2000, it became a rationale for annulling the reciprocal relationship that existed betwe een Google and its users, steeling the founders to abandon their passionate and public opposition to advertising.... To meet the new objective, the behavioral value reinvestment cycle was rapidly and secretly subordinated to a larger and more complex undertaking. The raw materials that had been solely used to improve the quality of search results would now also be put to use in the service of targeting advertising to individual users. Some data would continue to be applied to service improvement, but the growing stores of collateral signals would be repurposed to improve the profitability of ads for both Google and its advertisers. These behavioral data available for uses beyond service improvement constituted a surplus, and it was on the strength of this behavioral surplus that the young company would find its way to the "sustained and exponential profits" that would be necessary for survival. Thanks to a perceived cmergency, a new mutation began to gather form and quietly slip its moorings in the implicit advocacy-oriented social contract of the firm's original relationship with users.

...

In other words, Google would no longer mine behavioral data strictly to improve service for

users but rather to read users' minds for the purposes of matching ads to their interests, as

those interests are deduced from the collateral traces of online behavior. With Google's

unique access to behavioral data, it would now be possible to know what a particular

individual in a particular time and place was thinking, feeling, and doing. That this no longer

seems astonishing to us, or perhaps even worthy of note, is evidence of the profound psychic

numbing that has inured us to a bold and unprecedented shift in capitalist methods.

【題組】 1. Summarize Zuboff's argument in no more than 200 words. (40%)