活動名稱

【解題達人! We want you!】

活動說明

阿摩站上可謂臥虎藏龍,阿摩發出200萬顆鑽石號召達人們來解題!

針對一些題目可能有疑問但卻缺少討論,阿摩主動幫大家尋找最佳解!

懸賞試題多達20萬題,快看看是否有自己拿手的科目試題,一旦你的回應被選為最佳解,一題即可獲得10顆鑽石。

懸賞時間結束後,只要摩友觀看你的詳解,每次也會得到10顆鑽石喔!

關於鑽石

如何使用:

- ✔懸賞試題詳解

- ✔購買私人筆記

- ✔購買懸賞詳解

- ✔兌換VIP

(1000顆鑽石可換30天VIP) - ✔兌換現金

(50000顆鑽石可換NT$4,000)

如何獲得:

- ✔解答懸賞題目並被選為最佳解

- ✔撰寫私人筆記販售

- ✔撰寫詳解販售(必須超過10讚)

- ✔直接購買 (至站內商城選購)

** 所有鑽石收入,都會有10%的手續費用

近期考題

【非選題】

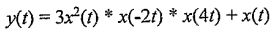

【題組】(a) (5%) What is the bandwidth of y(t)?

(4) Suppose that x(t) is real and has the bandwidth of W and where *means convolution.

where *means convolution.

【題組】(a) (5%) What is the bandwidth of y(t)?

Article 2

【題組】17. Which sentence is NOT the aim of "clean labe!"?

(A) Represented the natural food.

(B) Avoid food additives.

(C) Provide reliable information.

(D) Keep food safe.

(Source: Food Research International, 2017 99(1):58-71)

During the last century, industrialized countries have overcome lack of food

security with the key contribution of agrifood industrialization. Food processing has

played a crucial role as it allowed extending the shelf life of food products, reduced

food losses and waste, as well as improved nutrient availability and optimization.

However, day-to-day consumer perception focuses on other aspects than these

achievements. In modern societies, the increasingly globalized markets and greater

processing in the food chain has contributed to a perceived distance and knowledge gap

between people and food manufacturers (e.g. how food is produced, where is it

produced, etc.).

For instance, food contamination accidents have affected Europe in the last

decades, such as BSE and dioxin. Consu umers are concerned about the heavy use of

pesticides in the conventional and intensive agricultural practices, the use of artificial

ingredients, additives or colourants such as E133, and the adoption of controversial

food technologies like GMOs. This has prompted consumers to become skeptical or

worried about adverse health effects entailed in this food system. Moreover, the

growing public concemn about the contribution of the food system to climate change

and its overall negative effects on sustainability have led const

environmental and social consequences of food production.

The trends of healthiness and sustainability have triggered consumers into

considering which components are used in the food products that they cat in everyday

life. A new trend in food products has emerged, which is often summarized under the

umbrella of the so-called "clean labe!" and has been taken up by a multitude of food

industry stakeholders. The term clean label itsclf appeared for the first time during the

1980s when consumers started to avoid the E-numbers listed on food labels becausc

they were allegedly associated with negative health effects. The food industry has

started to respond to the increasing consumer demand of such clean label products by

supplying food products that are perceived as 'cleaner'. For example, in

2010 Heinz tomato ketchup was reformulated to remove high fructose com syrup from

the ingredient list and was renamed as Simply Heinz.

To date there is no an established, objective and common definition of what a clean

label is, but rather several definitions or interpretations, often provided by market trend

reports but not backed up by consu umer behavior re earch or theory. Ingredion (2014)

recommends to consu mers that "a 'clcan label' positioned on the pack means the

can be positioned as 'natural', 'organic' andor free from

additives/preservatives'" Edwards (2013) defines a clean label "by being produced free

of chemicals' additives, having easy-to-understand ingredicnt lists, and being produced

by use of traditional techniques with limited processing"' One of the key questions is

which ingredients may be part of a clean label, or, more importantly, which ingredicnts

define a clean label product by their absence. Busken (2013) proposes that the answer

to this depends on the consumer perception of an ingredient.

With regard to the clean label trend, we argue that hints about the item being a

clean label food are used as such cues. We argue that their casy usage and inference to

desirable, but unobservable characteristics explains the popularity of clean label.

Typically, consu umers might use cues found on the front of the package (FOP) such as

visuals indicating naturalness, organic certification logos, or free-from claims of

producers, thus, these products might be perceived as clean labcl. However, we argue

that not only peripheral processing is expected to play a role for clean label, but also

central processing. In some cases consumers might proceed to access information on

the back of the pack (BOP) in store or, even more likely, at home. There is a greater

likelihood that consumers who are engaging in this effort are characterized by greater

involvement and thus motivation to process, or that the situation at home provides better

opportunity to look at infornation and engage with it, thus, identifying the product as

clean labei. Therefore, central, more in-depth and conscious information processing

will occur more likely at home. Consumers might then look at the ingredient

information or nutrition facts more closely, and inspect and assess whether or not they

think the product is a clean label food in their opinion. However, given that consumers

might not find this easy to assess, they might nevertheless rely on heuristics, such as

the degree to which ingredient names sound chemical or are unknown, or the mere

length of the ingredient list. In addition to using this observable feature as a cue to a

product

desired quality, consumers might also favor products with understandable, short, known

and simple ingredient lists in order to reduce the cognitive effort needed in assessing

the product.

We suggest to define clean label, both in a broad sense, where consumers evaluate

the cleanliness of product by assumption and through inference looking at the front-of.

pack label and in a strict sense, where consumers evaluate the cleanliness of product by

inspection and through inference looking at the back-of-pack label. Results show that

while 'health' is a major consumer motive, a broad diversity of drivers influence the

clean label trend with particular relevance of intrinsic or extrinsic product

characteristics and socio-cultural factors. However, 'free from' artificial

additives/ingredients food products tend to differ from organic and natural products.

Food manufacturers should take the diversity of these drivers into account in

developing new products and communication about the latter. For policy makers, it is

important to work towards a more homogenous understanding and application of the

term of clean label and identify a uniform definition or regulation for 'free from'

artificial additives/ingredients food products, as well as work towards decreasing

consumer misconceptions.

【題組】17. Which sentence is NOT the aim of "clean labe!"?

(A) Represented the natural food.

(B) Avoid food additives.

(C) Provide reliable information.

(D) Keep food safe.

【非選題】

【題組】(b)Calculate the time required for half of A is reacted.

2. Consider a second order reaction A + B → P

, where the rate equation is d[P]/dt = k [A] [B] and [B]o= 2 [A]o = 2 a. (9%)

, where the rate equation is d[P]/dt = k [A] [B] and [B]o= 2 [A]o = 2 a. (9%)

【題組】(b)Calculate the time required for half of A is reacted.

8 依照強制汽車責任保險法之規定,請求權人得向特別補償基金請求補償之情形,何者錯誤?

(A)事故汽車為未保險汽車

(B)事故汽車肇事逃逸無法查究

(C)事故汽車係被保險人自撞之被保險汽車

(D)事故汽車係未經被保險人同意使用或管理之被保險汽車

(A)事故汽車為未保險汽車

(B)事故汽車肇事逃逸無法查究

(C)事故汽車係被保險人自撞之被保險汽車

(D)事故汽車係未經被保險人同意使用或管理之被保險汽車