題組內容

Pipelines, Platforms, and the New Rules of Strategy

Back in 2007 the five major mobile-phone manufacturers-Nokia, Samsung, Motorola, Sony Ericsson, and LG--collectively controlled 90% of the industry's global profits. That year, Apple's iPhone burst onto the scene and began gobbling up market share. By 2015 the iPhone singlehandedly generated 92% of global profits, while all but one of the former incumbents made no profit at all.

How can we explain the iPhone's rapid domination of its industry? And how can we explain its competitors' free fall? Nokia and the others had classic strategic advantages that should have protected them: strong product differentiation, trusted brands, leading operating systems, excellent logistics, protective regulation, huge R&D budgets, and massive scale. For the most part, those firms looked stable, profitable, and well entrenched.

Certainly the iPhone had an innovative design and novel capabilities. But in 2007, Apple was a weak, nonthreatening player surrounded by 800-pound gorillas. It had less than 4% of market share in desktop operating systems and none at all in mobile phones. As we'll explain, Apple (along with Google's competing Android system) overran the incumbents by exploiting the power of platforms and leveraging the new rules of strategy they give rise to. Platform businesses bring together producers and consumers in high-value exchanges. Their chief assets are information and interactions, which together are also the source of the value they create and their competitive advantage.

Pipeline to Platform

Platforms have existed for years. Malls link consumers and merchants; newspapers connect subscribers and advertisers. What's changed in this century is that information technology has profoundly reduced the need to own physical infrastructure and assets. IT makes building and scaling up platforms vastly simpler and cheaper, allows nearly frictionless participation that strengthens network effects, and enhances the ability to capture, analyze, and exchange huge amounts of data that increase the platform's value to all. You don't need to look far to see examples of platform businesses, from Uber to Alibaba to Airbnb, whose spectacular growth abruptly upended their industries.

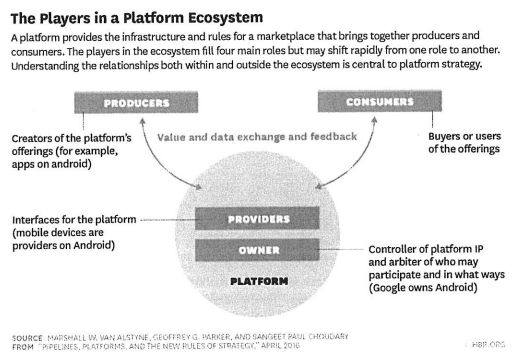

Though they come in many varieties, platforms all have an ecosystem with the same basic structure, comprising four types of players. The owners of platforms control their intellectual property and governance. Providers serve as the platforms' interface with users. Producers create their offerings, and consumers use those offerings (see Figure in the next page).

To understand how the rise of platforms is transforming competition, we need to examine how platforms differ from the conventional "'pipeline" businesses that have dominated industry for decades. Pipeline businesses create value by controlling a linear series of activities-the classic value-chain model. Inputs at one end of the chain (say, materials from suppliers) undergo a series of steps that transform them into an output that's worth more: the finished product. Apple's handset business is essentially a pipeline. But combine it with the App Store, the marketplace that connects app developers and iPhone owners, and you've got a platform. The move from pipeline to platform involves three key shifts:

1. From resource control to resource orchestration. The resource-based view of competition holds that firms gain advantage by controlling scarce and valuableideally, inimitableassets. In a pipeline world, those include tangible assets such as mines and real estate and intangible assets like intellectual property. With platforms, the assets that are hard to copy are the community and the resources its members own and contribute, be they rooms or cars or ideas and information. In other words, the network of producers and consumers is the chief asset.

2. From internal optimization to external interaction. Pipeline firms organize their internal labor and resources to create value by optimizing an entire chain of product activities, from materials sourcing to sales and service. Platforms create value by facilitating interactions between external producers and consumers. Because of this external orientation, they often shed even variable costs of production. The emphasis shifts from dictating processes to persuading participants, and ecosystem governance becomes an essential skill.

3. From a focus on customer value to a focus on ecosystem value. Pipelines seek to maximize the lifetime value of individual customers of products and services, who, in effect, sit at the end of a linear process. By contrast, platforms seek to maximize the total value of an expanding ecosystem in a circular, iterative, feedback-driven process. Sometimes that requires subsidizing one type of consumer in order to attract another type.